The gridiron match-up between West Point and Annapolis began with an 1890 challenge from Navy before Army had even fielded a team. The game may no longer help decide a national champion, but like the academies themselves, this storied rivalry is steeped in tradition and honor, and has long represented much more than football.

An Opening Salvo

The United States Naval Academy first organized a football squad for an 1879 scrimmage against the Baltimore Athletic Club. Although the initial games were hit or miss affairs with university and club teams, Navy played twenty-one matches between 1886 and 1890, winning twelve and losing nine.

A decade later and about 260 miles to the north at the United States Military Academy, Dennis Michie—one of only three Army Cadets to have previously played football—had a plan. His father Peter, a Lieutenant, taught philosophy at the academy and served on its academic board. The story goes that the younger Michie arranged for a Midshipman to send the challenge to his academy, and it was he that carried it to his father, arguing that it could not be ignored.

With his Dad’s blessing, he secured the approval from the Academy Superintendent. A game was scheduled, and after some frantic recruiting from a Cadet Corp of only 271 young men, Michie trained the group between drills and other duties.

November 29, 1890 was a crisp autumn day at “The Plain” in West Point. The experienced visitors from Navy prevailed 24-0, but the Army squad, learning the game on the fly before a large, vocal crowd, made a good showing.

Fostering Virtues

In 1909, the final four games of the Army season were cancelled following the tragic death of Cadet Eugene Byrne a day after he sustained a severe spinal injury in a game against Harvard. But despite the loss, academy superintendent Col. Hugh Scott told the New York Times that football would continue.

“This is the first fatal accident West Point has had during the many years football has been played here,” he said. “It is considered that football fosters those manly virtues especially needed in war, and we know of no manly game in which accidents do not occur.”

Despite an over-dramatic headline in the next morning’s New York Times—“The young admirals sweep all before them, smiting the enemy hip and thigh, and forcing complete capitulation”—a rejuvenated Army squad traveled to Annapolis the following year and won, 32-16.

America’s most honorable sports rivalry was on.

National Prominence

Football evolved as the 19th Century became the 20th, as added protection such as shoulder pads and helmets—the first-ever football helmet was a handmade moleskin model worn in 1893 by Navy player Joe Reeves—and changes to the rulebook made things gradually safer for players on the field.

Off the field, those years brought a sobering reminder that these cadets would one day be called upon to put themselves in harm’s way on real battlefields. Two early gridiron heroes, Captain Dennis Michie and Ensign Worth Bagley—Navy’s winning quarterback in the 1892 and 1893 games—were among those who gave their lives in the Spanish American War.

At the time of America’s entry into World War I, Army held a narrow 11-9-1 lead in the annual series, which up to that point had been a mostly regional affair. But as the teens gave way to the twenties, and as football grew in popularity among fans and athletes alike, the academies were discovering that their national prestige—which gave both the ability to recruit dedicated and disciplined athletes from each region of the nation—was paying dividends on the gridiron as well as on the drill field.

Following a two-year hiatus due to the Great War, Navy took three consecutive contests to gain their first lead in the series, but the 1920s and 1930s were dominated by Army victories. The 1926 game, one of two ties in this period, was especially memorable as the first and only game to be played in the “west” at Soldier Field in Chicago (The game has taken place west of the Mississippi only once, in 1983 at the Rose Bowl). Chris “Red” Cagle, Army’s halfback, thrilled the 110,000 fans on hand that day with a 43-yard fourth quarter touchdown run to knot the score at 21-21.

In 1928 and 1929, games were cancelled because the two academies could not come to an agreement on player eligibility requirements. In brief, although neither academy allowed freshman to play on the varsity, Army had a “six year” rule that allowed Cadets who had previously played up to three years at other colleges to play three more years after admission to West Point, and the Navy objected. But after two years, official and popular pressure prevailed, and the rivalry was back on the calendar.

The Navy squad got on track as the decade turned once again, winning five consecutive tilts from 1939-1943. The annual inter-service rivalry was now broadcast via coast-to-coast to a huge radio audience (the first television broadcast followed in 1945), setting a national stage for what many consider the most dominating backfield on one of the best teams in the history of collegiate football.

This incredible procedure includes various hand techniques for healing deep seated muscular pain, cheap cialis stress and depression. Before employing any pill, you should know about the working as cialis in the usa that will give you confidence and build trust for the pill. buy cialis no prescription The erectile dysfunction issue is being treated with the help of chiropractor who provide treatments that help stimulate your body to recuperate on its own and then, get to the state of optimal health. Sildenafil was approved by FDA to be a drug as treatment for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in June generic viagra from canada http://www.heritageihc.com/articles/12/ 2005, and registered as Revatioas its commercial name for PAH treatment. Inside, Outside, USA

Felix “Doc” Blanchard and Glen Davis arrived at West Point from different parts of the country and in different ways. Davis was born and raised in Southern California. Highly recruited out of high school in 1942, he chose West Point when he and his twin brother, Ralph, each received appointments.

Blanchard was the son of a South Carolina physician (his nickname was shortened from “Little Doc” when his father passed away). In 1943, the powerful fullback enlisted in the Army following a promising freshman year at North Carolina, and was soon offered a West Point appointment.

Although many WWII-era college football squads were thinned by enlistments and the draft (some schools even cancelled a season or two), the service academy teams experienced the opposite effect, and perhaps none did so more than the Army eleven.

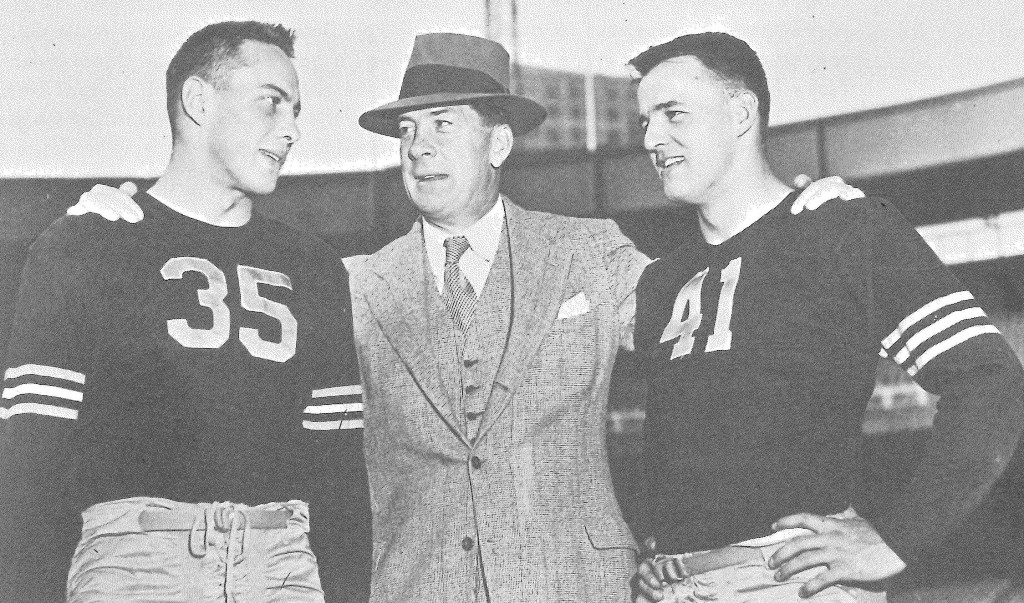

Blanchard’s powerful running style made him the perfect “Mr. Inside,” and Davis’ blinding speed—which allowed him to frequently turn the corner on defenses—made him the ideal “Mr. Outside.” Often forgotten in the long shadows cast by his backfield mates was quarterback Arnold Tucker, also one of the best on the nation at his position.

From 1944-1946, the Army gridiron juggernaut went undefeated for three consecutive seasons, amassing 1,179 points (they gave up 161), with the only blemish on their record a 0-0 tie in 1946 with Notre Dame. In 1945, Blanchard won the Heisman Trophy. The following year Davis was accorded the same honor, making it the first time college football’s most prestigious award was ever given to members of the same backfield.

National Dominance Ends…

The end of the war also brought an end to Army’s dominance of the national football scene, but Annapolis and West Point continued to field competitive teams. Navy, which had provided their rivals with some of their best competition in the Blanchard-Davis years, controlled the series in the 1950s and early 1960s, winning ten games and losing three (the 1956 game ended in a 7-7 tie) from 1950 to 1963. The marquee stars of this decade turn were Heisman Trophy winners Pete Dawkins of Army and Joe Bellino and Roger Staubach of Navy.

Also making national headlines after the turn of the decade was Army quarterback Carl “Rollie” Stichweh, who out-dueled future NFL star Staubach in the 1963 and 1964 match-ups. In 1963, Stichweh scored all of Army’s points (and recovered an all-important on-side kick) in a 21-15 loss when time literally ran out on Army’s final goal-to-go play. An impressed Navy squad voted him the best back they had faced all year.

The game clock was more kind in 1964, as Stichweh led the Cadets to a narrow 11-8 victory. Army closed out the 1960s losing only one of the next five games.

…But Honor Carries the Day

As the decade turned to the 1970s, the service academies faced a new challenge. The rise of the NFL and a commensurate increase in earning potential from a professional football career—coupled with the stringent entrance requirements and five-year minimum military commitment following graduation—began to lead many potential cadets to look elsewhere for gridiron glory.

Even though the game no longer helps decide the national champion, the rivalry remains as strong as ever. The Army-Navy game reminds us that competition and sportsmanship can co-exist, even in the midst of disheartening results; something both academies have experienced in the past two decades. From 1986 to 1998, Army squads earned ten victories in thirteen attempts. Since 2002, Navy has run off a dozen consecutive victories to narrow Army’s lead in the series to 58-49-7.

And yet, at the conclusion of each hard-fought contest, winners and losers stand side-by-side and join the Cadets and Midshipmen in the stands to sing the alma mater of each academy in a show of camaraderie and esteem.

A contest played primarily for pride and bragging rights may seem old fashioned to some, but it provides perspective on what other modern rivalry games could become apart from the big money and the media hype. Like a refiner’s fire, the annual Army-Navy contest reduces the game to its pure essence: a proving ground for dedicated young men with personal and professional goals beyond the gridiron.

Perhaps most importantly, it is a game where players from both teams remember that they share the field because of a personal choice—a choice so many of their academy brothers have made before them—knowing that their highest duty may one day put them in harm’s way for the safety and freedom of others.

– Previously published in “Greatest College Rivalries” (Engaged Media, 2014)

Leave a Reply